Help support children and families

Help support children and families

living with Biliary Atresia.

Continue below to read

Bianca Pengelly’s story.

When I was just two weeks old, I was diagnosed with Biliary Atresia, a condition in which the bile ducts in and around the liver are damaged. The damage means that bile can’t flow into the intestine, so it builds up in the liver and damages it.

When I was just two weeks old, I was diagnosed with Biliary Atresia, a condition in which the bile ducts in and around the liver are damaged. The damage means that bile can’t flow into the intestine, so it builds up in the liver and damages it.

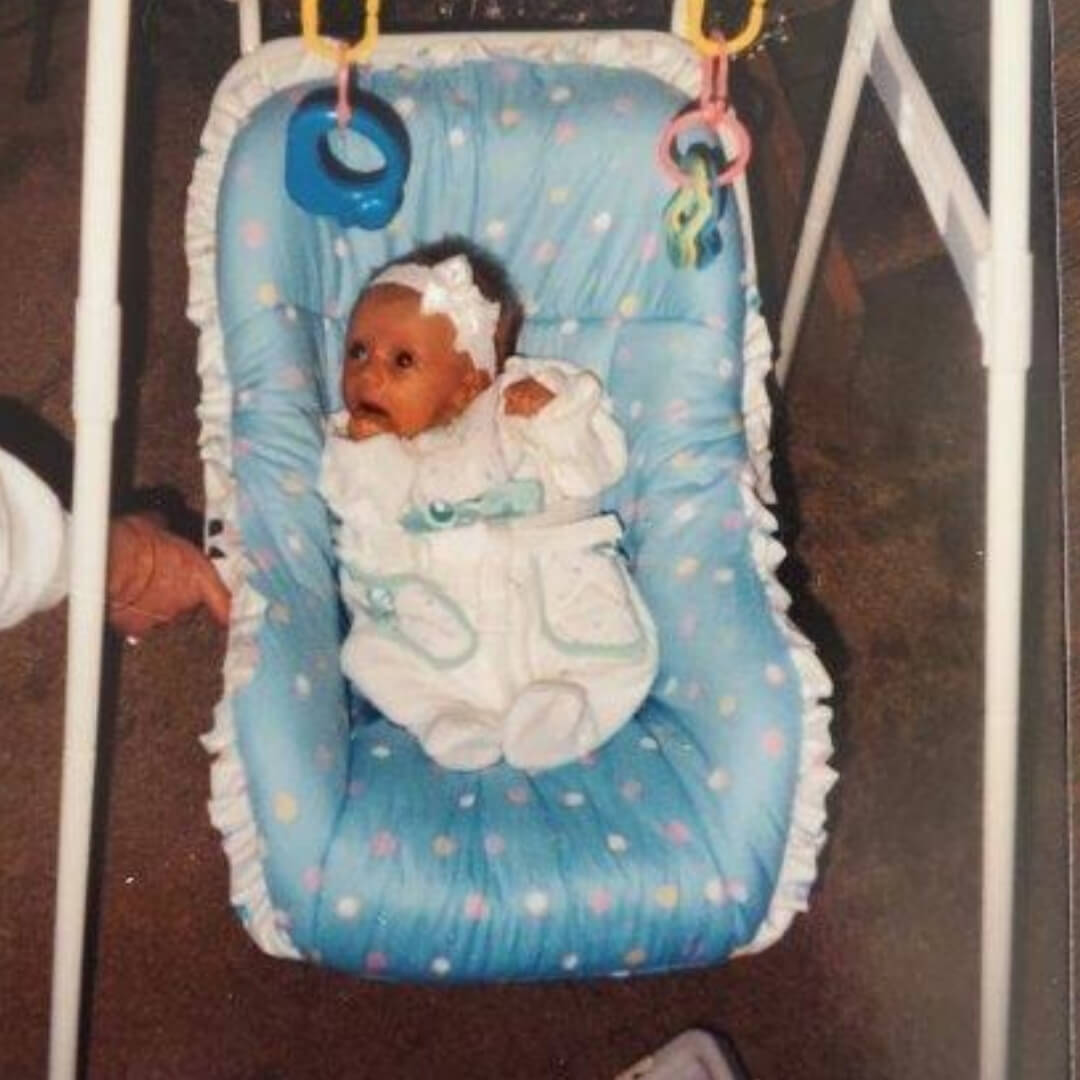

At the time of diagnosis, my parents were told that I would need a liver transplant but that my chances of survival were not good; waiting for a donor can be a long wait. I underwent a surgery called a Kasai procedure, which helps to drain bile from the liver. That was our best option for addressing my immediate need for treatment, but the procedure is not always successful, and we had no way of knowing if it would work for me.

The Kasai procedure was only the beginning. Keeping me healthy until a new liver was available became an every-day effort for my parents. I required special feeding formula and many liquid vitamins and antibiotics. If my temperature spiked, I was hospitalized, because a high fever could lead to complications—dehydration was a major concern.

The Kasai procedure was only the beginning. Keeping me healthy until a new liver was available became an every-day effort for my parents. I required special feeding formula and many liquid vitamins and antibiotics. If my temperature spiked, I was hospitalized, because a high fever could lead to complications—dehydration was a major concern.

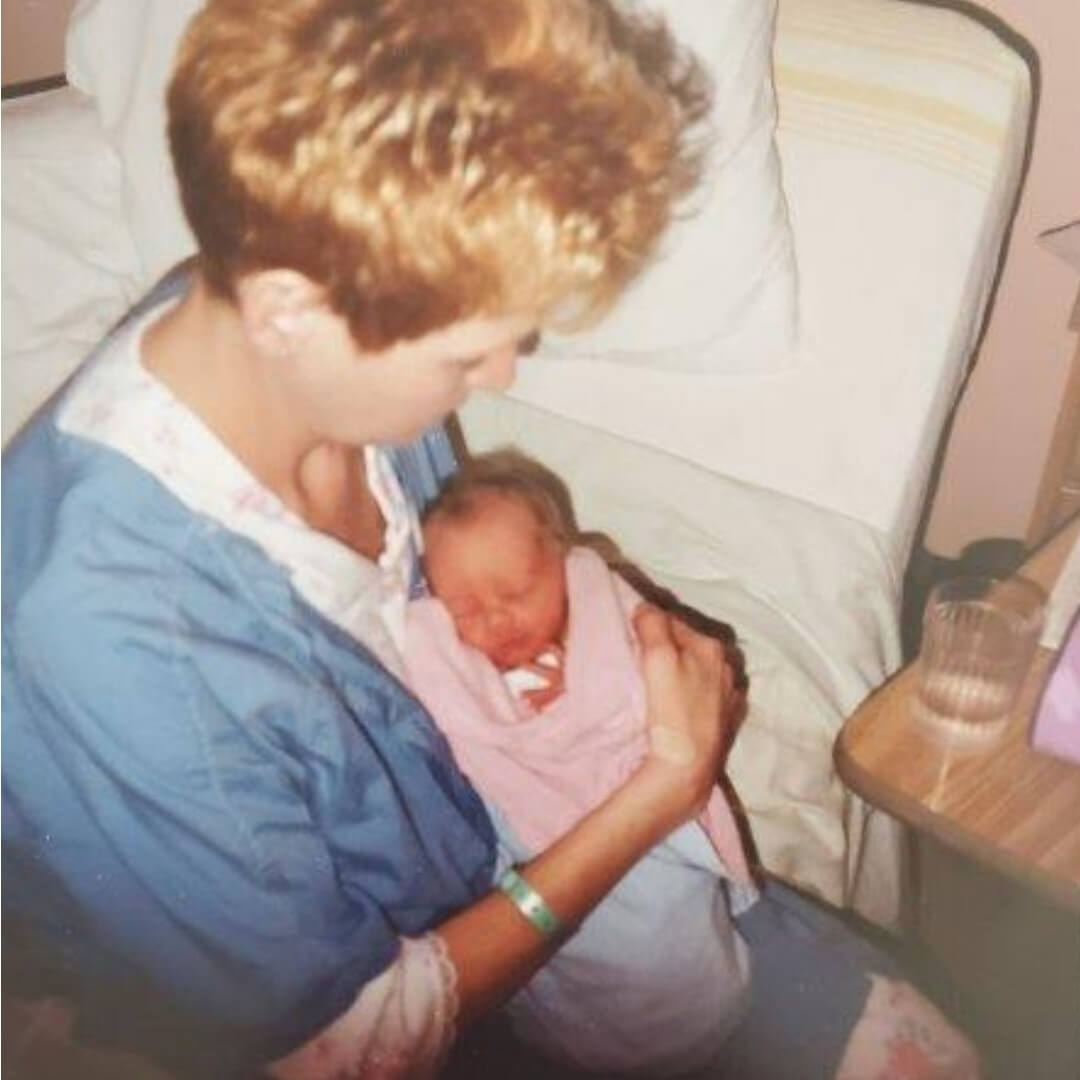

I was flown to Toronto for the full assessment that was needed to get me on the transplant list, and my parents were advised to prepare for the worst case scenario: the risk was very real that, while we waited for a donor, my disease could worsen and I might not be strong enough to withstand the transplant surgery when the time came. My mother made it her job to be cautious of any changes in my normal pattern, such as appetite, skin and eye colour turning yellow, fevers, and other things.

For those first 18 months of my life, my mother estimates that I spent roughly half of my life hospitalized. High fevers, appetite loss, and jaundiced skin were all frequent occurrences. She was even trained to tube-feed me to keep my weight up, so I was healthy enough for the transplant.

For those first 18 months of my life, my mother estimates that I spent roughly half of my life hospitalized. High fevers, appetite loss, and jaundiced skin were all frequent occurrences. She was even trained to tube-feed me to keep my weight up, so I was healthy enough for the transplant.

When I got on the transplant list, my mother was required to carry a pager at all times just in case a suitable donor become available. When I was 18 months old, we got the call. A match had been found, and off to surgery I went.

The call for my transplant brought up so many emotions for my family, and, to this day, my mother has trouble really putting her feelings about it into words. Perhaps the easiest one to express is her gratitude that someone made the choice to be a donor and save her daughter’s life. But there was always a sense of sadness, too, that another family had lost a loved one. And we all shed many tears, too, for other families who were still waiting for their donors.

While we were waiting for my transplant, my mother often told people, “Please don’t take you organs to heaven, because heaven knows we need them here.” And that is still just as true today; while I’m thankful for the happy outcome to my story, I often think about the many families that lose loved ones when donor organs aren’t available in time.

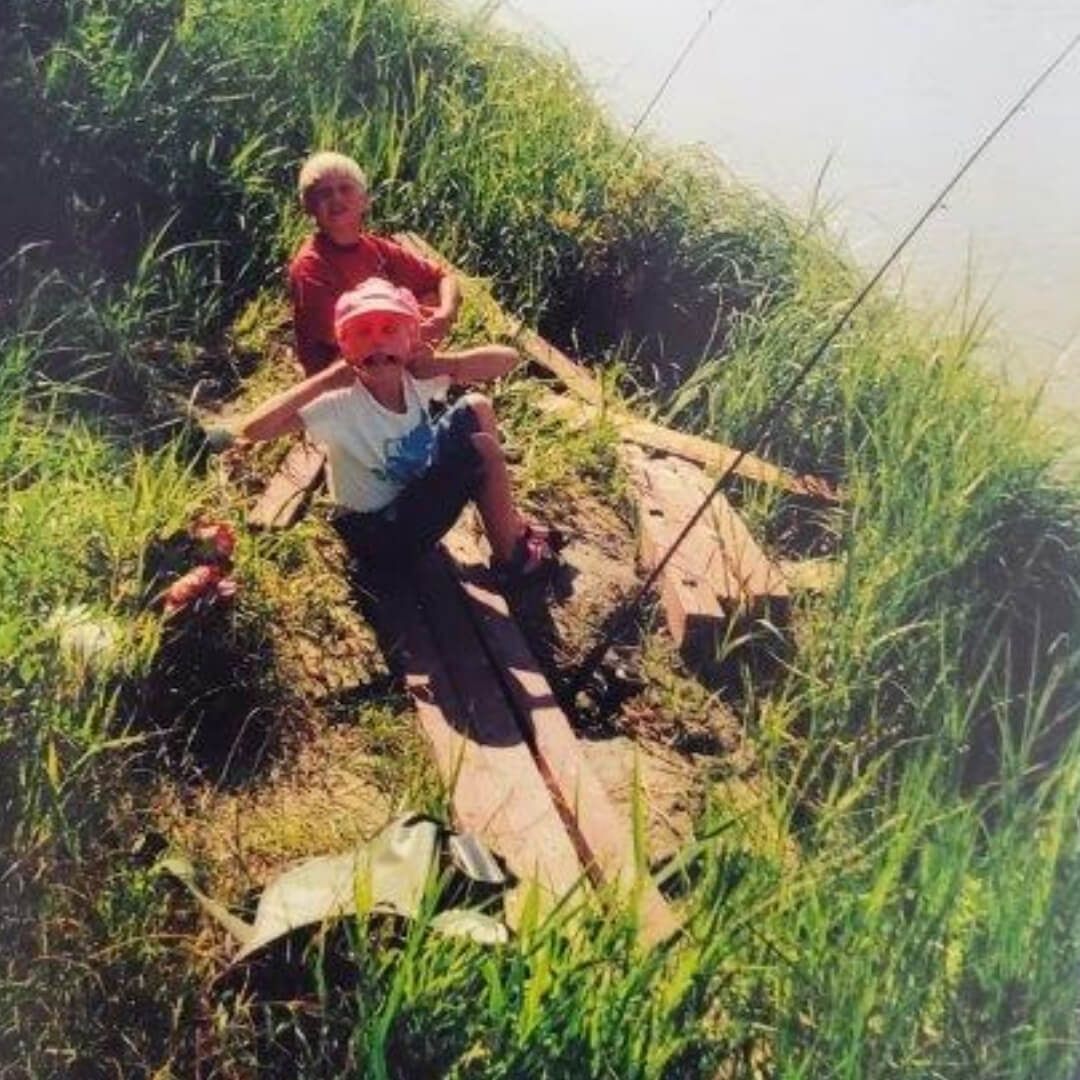

Today, I am a grown woman with two happy and healthy children of my own. While I do continue to have regular check-ups, I am off all anti-rejection drugs and every test comes back with remarkable results. No one would ever know that I live with a liver disease unless I told them. And I do tell them! I work as the Regional Coordinator for the Canadian Liver Foundation in Manitoba, and I often share my story to support those I meet who are now facing liver disease themselves.

Today, I am a grown woman with two happy and healthy children of my own. While I do continue to have regular check-ups, I am off all anti-rejection drugs and every test comes back with remarkable results. No one would ever know that I live with a liver disease unless I told them. And I do tell them! I work as the Regional Coordinator for the Canadian Liver Foundation in Manitoba, and I often share my story to support those I meet who are now facing liver disease themselves.

To the family that made the choice to give me a second chance: thank you. You are always in my thoughts. I’ve enjoyed a stable, successful life because of you.

This year, my family and I are Team Pengelly in the CLF’s Stroll for Liver. It is important to me to give back and raise funds for a cure to all liver diseases. Not everyone has a happy ending to their story; my own brother, whom we lost recently, battled liver disease himself for years. And the studies tell us that one Canadian in four—that’s more than eight million Canadians—are affected by liver disease, too, many of whom don’t even know it yet.

This year, my family and I are Team Pengelly in the CLF’s Stroll for Liver. It is important to me to give back and raise funds for a cure to all liver diseases. Not everyone has a happy ending to their story; my own brother, whom we lost recently, battled liver disease himself for years. And the studies tell us that one Canadian in four—that’s more than eight million Canadians—are affected by liver disease, too, many of whom don’t even know it yet.

My great hope is that a cure will be found soon so that liver disease doesn’t bring pain to anyone else.