Transplants

Organ Donation: The Gift of Life

For most people, a liver transplant is a life-saving operation. This operation involves replacing a diseased and poorly functioning liver with a healthy donated liver. A recipient may receive either an entire liver or a portion of a healthy liver. Liver transplantation has become a well-recognized treatment option for people with liver failure; in Canada, more than 400 such operations are performed every year! Livers are donated either from individuals who have been declared brain dead (with the consent of their next of kin) or from a living donor, such as a relative or friend. Liver transplant centres match donors with recipients based on compatible liver size and blood type.

Do you know someone who is celebrating their liver transplant or donor anniversary?

Click here to download and send a celebratory e-card.

The Transplant Process

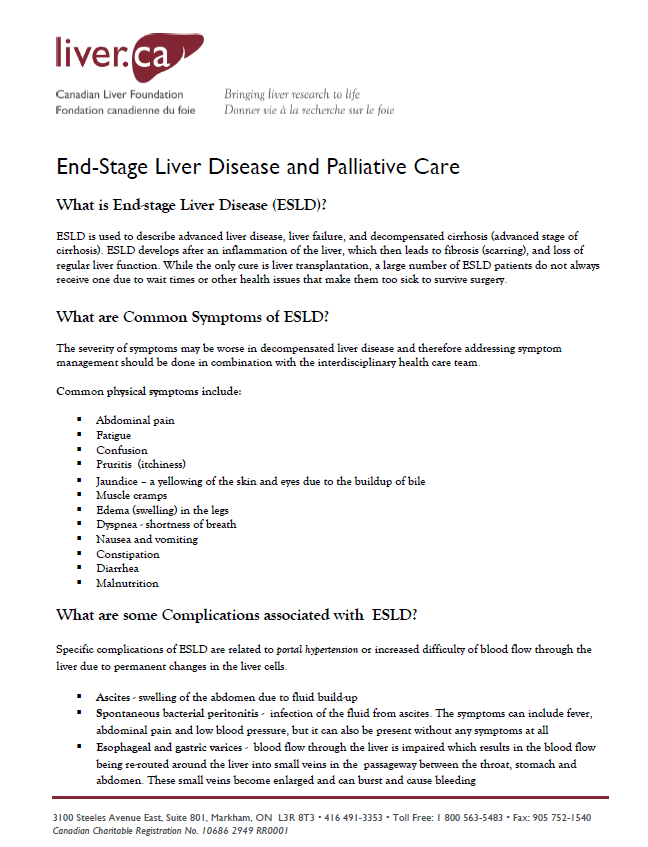

A liver transplant is a major surgery; the operation usually lasts between six and eight hours. Like any major medical procedure, liver transplantation has risks. These risks and the benefits are carefully considered before a patient is placed on the waiting list for a new organ. A successful outcome depends on many factors. For instance, patients who enter surgery when they are very ill have a greater risk of dying than those who are in better health. Similarly, older patients with cardiac or respiratory illnesses will find the transplant a greater challenge than younger patients who don’t have other health conditions.

A liver transplant is a major surgery; the operation usually lasts between six and eight hours. Like any major medical procedure, liver transplantation has risks. These risks and the benefits are carefully considered before a patient is placed on the waiting list for a new organ. A successful outcome depends on many factors. For instance, patients who enter surgery when they are very ill have a greater risk of dying than those who are in better health. Similarly, older patients with cardiac or respiratory illnesses will find the transplant a greater challenge than younger patients who don’t have other health conditions.

When medical therapy is effective in stopping the progression of liver disease, transplantation may be avoided or delayed. If a patient develops advanced disease with non-reversible impaired liver function, liver transplantation should be considered. Liver transplantation is not suitable for everyone, so all potential transplant patients must be carefully assessed. The assessment starts when the specialist or family doctor makes a referral to the transplant team. Patients receive a comprehensive medical evaluation, including various tests and interviews, by various team members to determine whether transplantation is the best treatment option. The patient and/or family members are extensively involved in the transplant assessment and decision-making process.

The waiting time for a new liver may be uncertain and stressful. The sickest patients receive a higher priority for a transplant. Prioritization is based on severity of the liver disease, measured by a Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score. In children, a modified scoring system, called Pediatric End-Stage Liver Disease (PELD) score, is used. If patients and families have difficulty coping during the waiting time, they are encouraged to seek assistance from a qualified health professional.

The waiting time for a new liver may be uncertain and stressful. The sickest patients receive a higher priority for a transplant. Prioritization is based on severity of the liver disease, measured by a Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score. In children, a modified scoring system, called Pediatric End-Stage Liver Disease (PELD) score, is used. If patients and families have difficulty coping during the waiting time, they are encouraged to seek assistance from a qualified health professional.

Before Your Transplant

Some people wait a long time for their transplant while others may experience a rapid decline in their health, leading to an urgent transplant. It is normal for patients and family members to feel a range of emotions during the transplant journey, regardless of the kind of path they are on.

Some people wait a long time for their transplant while others may experience a rapid decline in their health, leading to an urgent transplant. It is normal for patients and family members to feel a range of emotions during the transplant journey, regardless of the kind of path they are on.

Many people have positive emotions: hope, joy, and gratitude. But it is also normal to have difficult emotions, such as fear, sadness, anxiety, irritability, anger, and grief. It may be the patient who experiences strong emotions, or it may be their caregivers; anyone can experience stress and burnout during the transplant journey. Here are some common causes of stress for those who are being assessed or waiting for a transplant:

Feelings of Guilt—

- Thinking that someone has to die for you to receive an organ

- Feeling like you are a burden to others

- Blaming yourself for your disease

Lifestyle Changes—

- Experiencing symptoms of your disease, such as confusion, shortness of breath, low-blood sugar, dizziness or fatigue

- Living with the medical treatments and side effects that impact your quality of life (This might include taking new medications that have unpleasant side effects, monitoring your blood sugar and giving yourself insulin, having dialysis, or carrying oxygen tanks or mechanical devices.)

- Having a hard time following the recommendations made by your health team, such as physical activity guidelines, fluid or diet restrictions, or abstaining from alcohol or cigarettes

- Losing your sex drive or ability due to your physical condition, side effects of medication, changes in self-esteem, or emotional health

Fear and Anxiety—

- Worrying about what may happen in the future

- Worrying about having a long hospital stay

- Waiting for assessment results or to be placed on the transplant list

- Being called in for a transplant and finding out the organ was not a suitable match for you (false alarms)

- Being in denial that you need a transplant

- Fearing that death may come before a donor organ becomes available

- Worrying about not surviving the surgery or about potential risks

Social or Relationship Stresses—

- Losing control over your life (choices, careers, school, or time)

- Lacking support from family or friends

- Feeling isolated and alone, like no one else understands

- Experiencing financial problems

- Feeling helpless and dependent on others

Living with a Transplant

In Canada, the long-term success rate of transplantation for both adults and children is more than 80%. Immediately after surgery, patients are taken to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) where they are placed on a machine known as a mechanical ventilator, which supports their breathing. They are carefully monitored for signs of infection. Frequent tests are conducted to assess the functioning of the new liver. Most patients spend one to three days in the ICU before they are transferred to a step-down transplant unit. At this point, they are able to breathe on their own but will continue to have intravenous lines delivering medication. Following continued improvement and physiotherapy, patients usually leave the hospital after 10-14 days. They will be required to remain close to the transplant centre for several weeks and will attend an outpatient clinic for continued monitoring of their new liver. Most patients return to a good quality of life within three to six months after surgery.

All liver transplant patients must take anti-rejection medications for the rest of their lives. These are monitored to ensure the right amount of medication is present in the patient’s blood. These medications suppress the immune system, enabling the body to accept the new liver without attacking it. However, these medications also make all liver transplant patients more susceptible to developing infections. Infection prevention techniques are very important after receiving a transplant. There are many side effects associated with anti-rejection medications and they vary depending on the specific regimen a patient receives. Many patients experience some form of side effect during their course of treatment; however, many of the side effects are temporary or manageable. The risk of side effects also depends on the amount of anti-rejection medications required to protect the transplanted organ. The transplant team will often use the least amount of anti-rejection medications needed in hopes of avoiding or minimizing the risk of unwanted side effects. Furthermore, the transplant team monitors patients closely so that side effects can be identified and dealt with quickly.

All liver transplant patients must take anti-rejection medications for the rest of their lives. These are monitored to ensure the right amount of medication is present in the patient’s blood. These medications suppress the immune system, enabling the body to accept the new liver without attacking it. However, these medications also make all liver transplant patients more susceptible to developing infections. Infection prevention techniques are very important after receiving a transplant. There are many side effects associated with anti-rejection medications and they vary depending on the specific regimen a patient receives. Many patients experience some form of side effect during their course of treatment; however, many of the side effects are temporary or manageable. The risk of side effects also depends on the amount of anti-rejection medications required to protect the transplanted organ. The transplant team will often use the least amount of anti-rejection medications needed in hopes of avoiding or minimizing the risk of unwanted side effects. Furthermore, the transplant team monitors patients closely so that side effects can be identified and dealt with quickly.

After Your Transplant

Most liver transplant recipients are able to return to a normal and healthy lifestyle. Most report that they feel re-energized, have an improved quality of life, and enjoy everyday activities once more. Liver transplant recipients are able to participate in normal exercise after their recuperation, and women are able to conceive and have normal post-transplant pregnancies and deliveries. Despite successful surgeries, some liver transplant recipients may experience feelings of stress, anxiety, guilt and depression following their operation.

Most liver transplant recipients are able to return to a normal and healthy lifestyle. Most report that they feel re-energized, have an improved quality of life, and enjoy everyday activities once more. Liver transplant recipients are able to participate in normal exercise after their recuperation, and women are able to conceive and have normal post-transplant pregnancies and deliveries. Despite successful surgeries, some liver transplant recipients may experience feelings of stress, anxiety, guilt and depression following their operation.

Below are some common reasons that may cause stress in the time after your transplant:

Hospital-Stay Stressors—

- Feeling confused or disoriented after your surgery

- Staying in the hospital for a long time, maybe longer than planned

- Experiencing complications from surgery or new medical issues after your transplant

- Feeling pain and discomfort

Anti-Rejection Medications—

- Feeling the emotional side effects of anti-rejection medications, such as anxiety, confusion, depression, irritability, or trouble sleeping

- Noticing changes in how you look and in your self-esteem, both related to the side effects of anti-rejection medication

- Worrying about missing doses or taking the wrong medication at the wrong time

Feelings of Guilt—

- Feeling guilty about having depression or anxiety after your transplant

- Being unsure of how to fully express gratitude or feeling indebted to your living donor or to a deceased donor’s family

- Feeling guilty about receiving an organ, knowing others who may have passed away while waiting

- Wondering where the donor organ came from

Adjustment to Life After Transplant—

- Feeling too dependent on others and wanting to get back to being independent

- Feeling that your recovery is slow and that it is taking a long time to get your physical strength back to normal

- Feeling worried about leaving the hospital and returning home

- Feeling that your family or friends do not fully understand what you have gone through

- Living with a suppressed immune system

- Dealing with new lifestyle restrictions on activities like travelling, eating, taking supplements, or being out in the sun

- Fear of organ rejection

- Fear of infections and illnesses

We are all unique and have different ways of dealing with difficult times in our lives. It is common for patients and families to forget about taking care of their emotional and mental health during the ups and downs of their transplant journey.

Learning strategies to help you cope with difficult emotions, thoughts, physical health issues, and life circumstances can help to reduce stress. Here is a list of some ways you can manage your stress related to your transplant:

Balance Your Perspective—

- Some people say that “someone has to die for me to live” when they think about transplantation. But the reality is that people pass away every day. The families who donate organs often feel a sense of joy and relief that their loss can save the lives of others.

- Recognize that some of these changes are temporary. While it may take a few months after a transplant to feel ‘normal’ again, things will get better over time.

- Try not to compare yourself to other patients. Everyone’s transplant journey is different.

- Try to challenge unhelpful or worrying thoughts with more realistic ones. For example, instead of thinking, “What if I get sick and miss another family dinner?” say to yourself, “I have been taking my medications, and at my last clinic visit I was told that I was doing well. My family loves me and they understand my medical issues. Even if I do get sick, I can still video chat them.”

- Be kind to yourself. Remember: you have gone through a lot already! Only you really know how much you’ve been through!

- Try to keep your sense of humour, even during difficult times.

- Accept what you can’t change and that you might have to temporarily give up some of your day-to-day roles and responsibilities.

Take Control of Your Health—

- Consider using technology to track, organize, and set reminders about appointments, taking medications, tracking your weight or physical activity.

- Keep track of your health records and appointments.

- Use a pillbox or organizer to keep track of your medications, or ask your pharmacist to put your medications in a blister pack to make things easier.

- Learn about the common side effects of transplant medications. Knowing what to expect will help you to know when to take action and seek care or support.

- Take the lead on your health. Advocate for yourself by speaking to your medical team about any questions or issues you are experiencing related to your emotional or physical health.

- Seek out rehabilitation options and exercise within your limits.

- If you smoke, take steps to quit smoking by joining a smoking cessation program or asking your primary care provider or pharmacist for support.

- Seek help if you or your family is worried about your drug or alcohol use.

Self-Care—

- Try out new, meaningful activities and hobbies within your physical abilities. Or, revisit an old hobby that brings you joy.

- Make healthy sleep habits a priority.

- Write down your experiences to reflect on later or to share with others.

- Practice mindfulness or yoga at home, at a studio, or at a community centre.

- Try relaxation strategies, breathing exercises, and meditation or grounding skills.

- Get creative! Try out adult colouring books, playing or listening to music, painting, or other arts and crafts to relieve stress and express your feelings.

- Try and find a small pleasurable activity or do something kind for yourself every day, even if it seems small.

- Use health and wellness mobile apps to keep you on track and manage your symptoms and health.

Give Back—

- Consider volunteering your time or giving back to the community in some way. For example, find out if there is a high school outreach initiative to raise awareness about organ donation.

- Think about writing an anonymous letter to your donor. Ask your transplant coordinator for help if you are having difficulty writing your donor thank-you letter after transplant.

- Share your appreciation with your caregivers and the healthcare team. For example, you might wish to send a card, letter, or simply say ‘thank-you’.

Connect with Others—

- Talk to your loved ones about how you feel.

- Share your story with others.

- Spend time with the people who matter to you the most.

- Join a local or online support group.

- Find a community through social media, such as Facebook, Instagram or Twitter.

We urge you to speak to your healthcare team if you are not feeling like yourself or are feeling depressed or anxious. Your local healthcare team is available to provide emotional and practical support to patients and families before and after transplant. Ask your transplant coordinator or doctor for a referral.

Spiritual Care

There are also spiritual care practitioners who are available to offer support. Let your local healthcare team know if you would like to connect with a spiritual care practitioner.

Help in the Community

In some cases, healthcare teams can set up telehealth network appointments for urgent consultations with the transplant healthcare team. Your local healthcare team or transplant coordinator can also help you find local resources and support as you cope with the stress of transplant.

Finding Help Yourself

Here are some suggestions for seeking additional support on your own:

- Speak to your primary care provider (family doctor or nurse practitioner) about support resources in your community.

- If you are a patient of a Community Health Centre or Family Health Team, ask if there is a social worker who can help you navigate community support.

- Find a social worker to speak to. They can help you to access financial support, drug coverage information, and other helpful resources.

- Join a support group in the community for people living with organ disease, chronic illness, or transplant.

- Join an online support group, or find a community of people to connect with on social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter

- Visit your local healthcare library and speak to a librarian. They can help you to find information about your condition, healthy living, and more. You can pick up brochures or borrow books and eResources.

- Connect with spiritual or religious leaders in your community for support and guidance.

- Seek out a counsellor or therapist.

- Ask your care team for a referral to a local Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program.

Being a Liver Donor

The long waiting time for a liver transplant and the progression of the liver disease that occurs during this period has motivated many families to consider living donation. It should be noted, however, that not all candidates are suited for this option. Liver transplant centres match donors with recipients based on compatible liver size and blood type.

The long waiting time for a liver transplant and the progression of the liver disease that occurs during this period has motivated many families to consider living donation. It should be noted, however, that not all candidates are suited for this option. Liver transplant centres match donors with recipients based on compatible liver size and blood type.

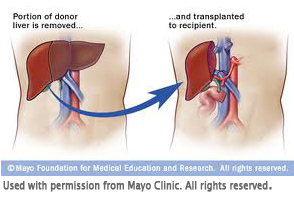

In babies, living donor transplants involve transplanting a small portion of the left lobe of the adult donor’s liver to an infant. Adult-to-adult living donor transplantation is achieved by using the entire right lobe of the donor’s liver. Not all potential donors are suitable for living donation, and extra precautions are taken by the transplant team to ensure that the decision to donate is without coercion and is unconditional. The living donation operation is a major surgery and requires a five to 10-day hospitalization and two to three month period of recovery. However, the donor surgery has a very low risk of death, and, within a few months, the donor’s liver regenerates to within 90% of its original size.

Advantages & Risks of Being a Living Liver Donor

Advantages

- Provides a lifesaving transplant, scheduled at time convenient for the donor, and with minimal waiting time for the recipient

- Provides an opportunity for the donor to give “the gift of life,” with a faster return to good health and good quality of life for the recipient

- Removes a person from the deceased liver wait list and increases organs available for transplant

- Allows donor to feel deep satisfaction from their act of kindness and generosity

Risks

- Requires all parties to recognize that not all transplants are successful

- Calls for a major operation, and, although living donors are in good health, there are risks related to having surgery (The transplant team will address the potential candidates about the risks involved.)

- Requires multiple visits to the hospital for evaluation and a recovery period of at least six weeks.

- Involves financial responsibility, with only part of the costs associated with surgery being reimbursed by the certain provincial governments

Liver transplantation is available to all residents in Canada. Each province has a multi-organ transplant program, however, not all programs perform liver transplant surgery. All multi-organ transplant centres are able to initiate a living liver donor assessment process. For a list of multi-organ transplant centres and organ procurement organizations in Canada, visit the Canadian Society of Transplantation.

The organ donation process and the requirements for becoming a living liver donor differ between multi-organ transplant centres across the country. If you are interested in becoming a living liver donor, it is important to speak with your healthcare professional and contact your local multi-organ transplant centre or organ procurement organization for details. We have provided some frequently asked questions below:

Frequently Asked Questions

A living liver donation means that someone who is living gives part of their liver to someone waiting for a liver transplant. The person who gives their liver is called a ‟donor.” The person waiting for a liver transplant is called a ‟transplant candidate” or ‟recipient.” Living donation is another way for someone to get a liver transplant, however it is not always possible. Some recipients decide that living donation is not the right choice for them because of the risks or other personal reasons.

- There is a shorter waiting time to receive a healthy liver.

- The transplant is done while the recipient is still reasonably healthy and able to have a faster recovery.

- There is a lower risk of the recipient dying or being disqualified while waiting.

- A high-quality donor organ is assured.

- Live donors must be completely healthy to donate (as opposed to deceased donors for whom a complete health history is not always available or whose history indicates previous health issues existed; due to the lack of organs available for transplant, oftentimes there is a need to use deceased donor livers that are less than ideal in order to save a life).

- The donor and recipient can plan for the elective surgery.

- It is a chance for the donor to “give the gift of life” to a family member or friend.

Becoming a living liver donor is an option for healthy people who are, typically, 16-60 years of age. They must be in good general health with no evidence of significant high blood pressure, diabetes, cancer, liver disease, or heart disease, and they must be a blood type match to the recipient. A living liver donor can be a family member, a friend, or a stranger (anonymous). In some cases, it is possible for a person who is not a blood type match to donate to a recipient. If you want to donate a part of your liver to someone but are not a blood type match, you can still go through the donor assessment process. The transplant team will then decide if this is an option for you and your recipient.

Your local living liver donor transplant office or procurement organization provides information about the donation and organizes the donor assessment process. Many tests are done, such as blood tests, a CT scan, and an MRI to find out if someone can be a living donor. The donor meets with the donor team members (surgeon, doctor, and psychiatrist) several times. The living liver donor team helps to find out if living liver donation can be done and makes sure it is the right choice for the potential donor. If the potential donor is in good health and a good match, planning for surgery begins. A date for the surgery is chosen, and the living donor team talks with the donor about final details.

The donor surgery lasts about six hours. The surgeons remove about half of the donor’s liver, which is transplanted into the recipient soon after. Within six to 12 weeks, the donor’s liver regrows to about 90% of its original size and starts to work normally again. The hospital stay for donors is about five to seven days. Donors can usually return to work after six to 12 weeks.

Yes, in most cases, you will have to pay any non-medical costs, such as travel expenses, out-of-pocket costs, and any applicable child care costs. You may also have a loss of salary for time off work during recovery from the surgery, unless you have sick-leave coverage from your employer’s company health plan. However, some provinces reimburse some of the non-medical expenses, which is why it is important to speak to the social worker or the transplant health team to find out more.

First, learn as much as you can about the living liver donation process, and find out what your blood type is. Then, speak with your healthcare provider and contact the transplant center that is taking care of the potential recipient to arrange testing to confirm whether your blood type is compatible. From there, the transplant center staff will lead you through the process.

Like any major surgery, there is a chance that some complications may happen, including:

- Problems with the anesthetic

- Wound infections

- Pneumonia (lung infection)

- Possible blood clots in the lungs or legs

- Bleeding

- Bile leakage

- Mental stress

- Other life-threatening complications.

The transplant health team will talk with the donor about all these risks before the surgery.

Yes, you can change your mind at any time during the process, and your decision will be respected by the transplant health team. They will also help you communicate your decision to the potential recipient.

Provincial Programs and Organ Procurement Organizations:

- Alberta — Southern Alberta Organ and Tissue Donation Program

- British Columbia — BC Transplant Program

- Manitoba — Gift of Life Program

- Newfoundland and Labrador — Organ Procurement and Exchange of Newfoundland and Labrador

- New Brunswick — New Brunswick Organ and Tissue Procurement Program

- Nova Scotia — Multi-Organ Transplant Program

- Ontario — Trillium Gift of Life Network

- Prince Edward Island — Multi-Organ Transplant Program of Atlantic Canada

- Quebec — Transplant Quebec

- Saskatchewan — Saskatchewan Transplant Program

- Anxiety Canada — promotes awareness and offers resources

- Canadian Mental Health Association

- 211 Government and Community resources — also dial 2–1–1

- Positive Coping with Health Conditions — free workbook to learn to cope with health conditions

This program will review what you need to know about medications after transplant. This includes why you need to take medications after a transplant, how to make sure you take the right dose of your medications, and how to manage your medications safely and effectively at home. Please visit: http://pie.med.utoronto.ca/tmitt/index.html